This little book is only 98 pages long. And it is about trust. So! It does what it says on the tin.

The Thin Book of Trust: An Essential Primer for Building Trust at Work, 3rd Edition

Charles Feltman; 2008, 2021, 2024, Berrett-Koehler

The Thin Book of Trust showed up on a “Recommended for You” list, and I noticed that it was blurbed — and pretty enthusiastically at that — by Brené Brown. Seemed worth a shot.

And I quite enjoyed the read. I think the subject matter is important and too seldom addressed quite this directly.

There wasn’t much that I found particularly new in this book. But I think that’s on purpose. In fact, the first line of the “Acknowledgements” section is:

“There are no new ideas in this book; I can claim only their unique arrangement and expression.”

It’s true.

The subtitle pitches the book as “An essential Primer for Building Trust at Work.” So it wears its “basic building blocks” approach on its sleeve. And that’s good. Other than a brief and very high-level foray into the neurobiology of trust toward the end, there is precious little here that is technically advanced in any way.

At the risk of overstating it, some parts give off a slight whiff of: “John lied to Susan. Now Susan doesn’t trust John. Don’t be like John.”

But if most of the book’s content seems to be obvious common sense, I think the author would say, yeah, that’s the point. There’s no secret technique, there’s no magic formula. There’s just hard work, vulnerability, forgiveness, uncomfortable conversations, and ultimately, more rewarding and mutually beneficial relationships.

Trust people. Be trustworthy. Done. I made “thin” even thinner!

But there are several things this book does really well in its compact offering, and a couple of deceptively novel propositions for dealing with trust in the workplace.

“Trust allows us to disagree, debate, and test each other’s thinking as we work together to find the best ideas and solutions. Having work relationships built on trust allows us to get better and faster results with less stress.”

First, I appreciate the focus: it is very specifically about trust in the workplace. Much (most!) of what the book has to say about building, losing, and/or restoring trust seems like it would be widely applicable in all areas of life. But maintaining the narrow concentration on professional teams and co-worker relationships provides a valuable tightness and concision.

It could easily have attempted the opposite: a general approach to trust that also included notes about its application to a professional environment. That would have been much less wieldy.

Also, Feltman breaks down the overarching subject of “trust” into four “distinctions” (that’s the somewhat awkward word he uses, though he also sometimes uses “domains” and “dimensions,” so whatever). These are: care, sincerity, reliability, and competence.

I like this model a lot. Trust is not all-or-nothing, and this allows for a more nuanced discussion of where trust might be breaking down, an acknowledgement that a lot of relationships are complex combinations of trust and distrust, and a much more targeted approach to addressing the issue:

“Having someone’s limited and conditional trust is better than having them distrust you, but that also means you have to negotiate each transaction.”

These four domains appear in analyses of both one-on-one trust situations and team-wide trust, though the author notes some subtle but important differences between inter-personal and inter-group dynamics. A fair amount of this content is also specifically tailored to issues in management and leadership, which felt quite relevant to me.

“Being sincere takes intention, attention, and dedication, as does cultivating any aspect of trust in a complex, fast-paced environment with sometimes competing commitments.”

I especially appreciate the book’s focus on intentionality. That is one of my pillars of healthy workplaces, too: be intentional about what you do, and be honest about being intentional! Here, it’s specifically about being intentionally trustworthy — and intentionally willing to trust. It’s about intentionally addressing issues when they come up, and even about intentionally remarking about when things are going particularly well.

Basically: try to be conscious and present and do things on purpose. And if you make a mistake, make it right.

Unsurprisingly given its remit, a great deal of the book is dedicated to advice, tools, and techniques for improving communication. There are actually some really helpful, realistic, actionable tips in here. None of it is particularly ground-breaking (I have covered some of the same ground), but it is useful and pertinent.

Look, if we’re being honest, most of the advice boils down to, “don’t be a passive-aggressive douchebag.” But hey — that’s good advice!

At one point it feels like Feltman shows his hand a little, as it were. When discussing how difficult some of this communication can be he says:

“Engaging a skilled team coach or facilitator can be well worth the cost.”

I don’t doubt that’s true, but it’s hard not to seem just a bit self-serving, isn’t it? That’s what this guy does for a living!

“Numerous studies confirm what most of us know from experience: strong trust is part of the fabric of high performing teams.”

This book is based very much on the author’s own experiences and observations, both in organizations and as a consultant and trainer to organizations. In that sense it’s largely “original research.”1 He does occasionally pull in other work, though.

For instance, he cites studies which demonstrate that trust throughout an organization is literally good business:

“Tony Simmons, the Lewis G. Shaeneman Jr. Professor of Innovation and Dynamic Management at Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration, researched the effect of trust on a company’s bottom line.

Even a very small improvement in a hotel’s score on Simmons’s scale could be expected to increase its bottom-line profit significantly.

As Simons’s studies and other research on employee engagement show, maintaining high trust at work creates a direct value.”

To be honest, I mostly wanted to quote that passage because I think that dude’s title is wild. But really, it’s an important point.

We’d all rather work in an environment of mutual trust. Of course! But generating the corporate will to foster and nurture that kind of environment requires demonstrating that it generates better business results. Because capitalism. So great! I’m happy this data exists.

Anyway, on the subject of citations I’ll note, as I always do when appropriate, that the relatively few citations this book has are handled beautifully with endnotes! Hooray! (I don’t want to die on this hill, but it feels like that is to be my fate.)

The book does have some strange quirks — perhaps a consequence of being a niche title put out by an independent publisher.

The tone is…relentlessly sincere. Nothing wrong with that, of course, and a welcome contrast to some recent books I’ve written about. Nonetheless its pastel-cardigan earnestness wears a bit thin. Maybe a little levity wouldn’t hurt?2

Also, the information design of the book is somewhat perplexing. There are bulleted-lists, call-out boxes, sometimes chapter subheadings (but sometimes not), inset lists, and tables. And exactly one illustration.

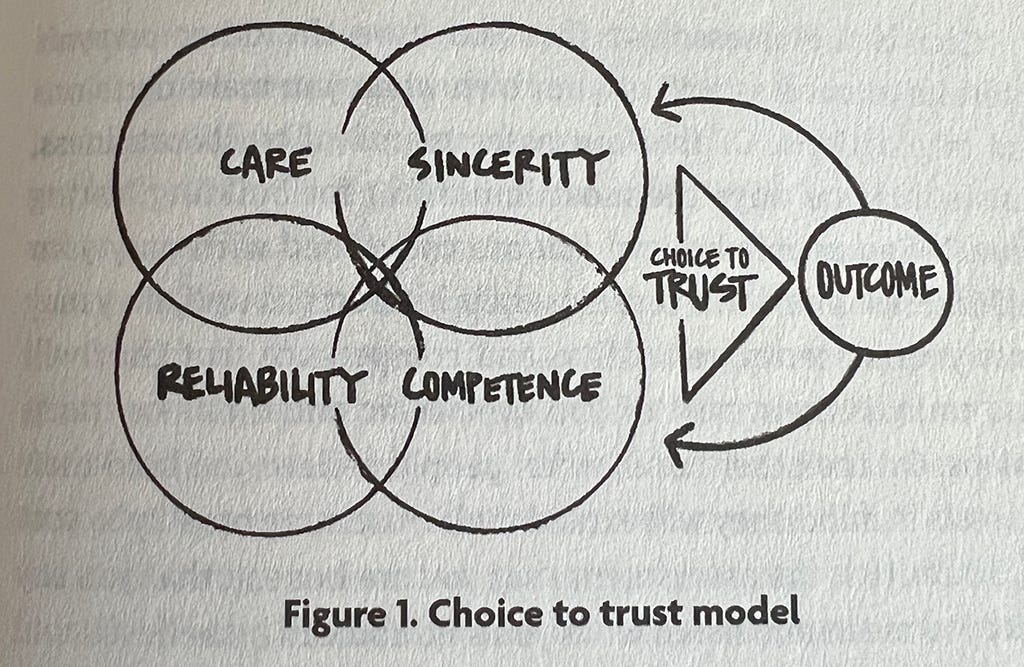

From the first chapter, this is the single graphic diagram to appear anywhere in the book:

I have no idea what that is supposed to be demonstrating. Well, I mean, I read the book: I do have some idea what it is supposed to be demonstrating. I just don’t think it’s helping much.

I think it’s trying to illustrate that there’s a feedback loop in trust/distrust decisions. Fair enough! But why the Venn-diagram-esque circles, followed by a flowchart symbol (sort of — the flowchart symbol for a decision is traditionally a diamond, not a triangle), followed by…I guess some curvy arrows that point at nothing in particular? It’s a poor example of a visual representation of the text, and since it’s literally the only one in the book, it really stands out.

Meanwhile, a couple chapters later, the author is talking about what he calls the “Cycle of Commitment.”3 This would make a great visual! The stages of this cycle could be easily illustrated, and communicate the whole concept effectively at a glance.

But, alas, it’s just a set of paragraphs with some initial italics for each one…which itself is literally the only instance of that layout design to appear anywhere in the book. Go figure.

It’s worth noting though, notwithstanding the lack of visuals, I found this Cycle of Commitment section to be terrific: a really fresh way of thinking about how trust can be built up or broken down through the process of committing to requests for action. Really on-point stuff.

And anyway, I don’t want to over-index on the presentation. I suspect that all the different designs are used because the book is trying to hit a broad swath of readership in a compact format; different people consume information in different ways, let’s give ‘em a smorgasbord. Okay, that’s a noble enough pursuit. I just think it isn’t very successful in this case.

“You might ask, Which comes first, trust or camaraderie? My experience is they build on each other over time as team members encounter each other at increasingly deeper levels of vulnerability and intimacy and experience repeatedly that each member does have the best interests of the others, the team, and the company at heart.”

I tend to agree with the fundamental notions of this book: that trust in the workplace is an absolutely critical element for a healthy, high-performing team; that trust is hard to develop (and valuable!), and perilously easy (and expensive!) to destroy; and that successfully nurturing it is virtually impossible by chance — it requires conscious, purposeful intentionality.

The Thin Book of Trust is frankly a little more self-help-y than most of what I read and write about for Ars Pandemonium. I’m not focused on textbooks or business administration dissertations, of course, but this felt even a little lighter-weight than usual.

But noting that the book covers some pretty…let’s say, obvious ground is hardly a critique. It’s a quick read, and while it didn’t reveal to me any great insight, neither did it insult my intelligence or ring untrue in any way.

Any and all of us can stand to be reminded of what we already know, pretty much all the time.

I’m not sure I agree with the subtitle that the book is “essential,” but I’m glad to have read it and will keep it around.

It doesn’t strike me as particularly rigorous academically or journalistically, say, but it seems well thought through.

There was exactly one instance of a wink-wink that I noticed in the entire book, and even that was pretty dad-joke-adjacent. When talking about the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of “direct” vs. “indirect” requests, Feltman gives several examples of the indirect variety. He then notes: “Even though none of these examples are technically requests, everyone (with the possible exception of teenagers) understands the intention behind them.” Ah, those teens, amirite?

See what I mean about that tone of sincerity?