The Ars Pandemonium Bookshelf

Thoughts and musings on mainstream business literature through my own prism of managing and leading teams of creative professionals. These are not “book reviews!” See more here.

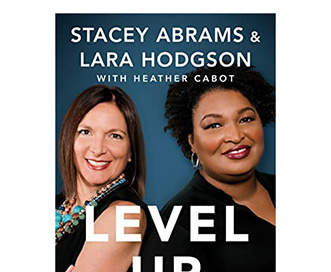

Level Up: Rise Above the Hidden Forces Holding Your Business Back

Stacey Abrams and Lara Hodgson with Heather Cabot; 2022, Portfolio/Penguin

Let’s be clear from the start: I picked this book up primarily because I’m a Stacey Abrams stan. I just think she’s nifty. Besides following her political career, I had been aware that she is an author — but I didn’t know she’s also a serial entrepreneur! Because I’ve been particularly seeking out management and leadership literature by and about women — and especially women of color — I was very excited to read it.

Overall, it was an easy and enjoyable read. It features an unusual framing device: it recounts the failure of a business founded and run by Abrams and her co-author and business partner Lara Hodgson. That’s an interesting twist! Along the way they examine what went wrong and uncover a number of systemic issues arrayed against entrepreneurs, especially those in marginalized or underrepresented communities.

I was particularly intrigued by certain insights into scaling a business where an individual person (or their time) is actually the product being sold. This has come up for me many times in my work as a consultant, sole-proprietor, and even as a team-of-one in some circumstances. Your business is truly successful, they posit, when it makes money for you while you sleep.

They write,

“Scaling a professional service business is hard because you are the product and your unit of value is time. Neither scale. To make money while you sleep, you will need to acquire other people’s time or develop a deliverable not measured by time.”

Of less specific, personal relevance to me were the discussions of cash flow, capital markets, retail partnerships, etc. Interesting to read about, but not exactly applicable to my project with Ars Pandemonium here.

And ultimately, it becomes clear in the final couple chapters that the book is actually mostly an ad for the authors’ new consulting venture. But, it’s hard to be mad about that: if you can get someone to pay for your company’s publicity with a book deal, that seems pretty smart!

“You don’t know what you don’t know. Focus on finding the right questions over finding answers.”

The insight and advice here is nominally aimed at small businesses (or “microbusinesses” as the authors also have it), but to me, some seemed quite relevant in the context of larger teams and companies, too.

Take, for instance, the observation that “often, small-business owners have to take advantage of opportunity when it arrives — not when they are ready.” This notion of maintaining a kind of background readiness to embrace opportunism is just as applicable when leading an in-house team as it is for an entrepreneur, in my experience.

And similarly, they note that,

“for most small businesses, the array of talent available comes with strings attached. The perfect person tends to already be on someone else’s payroll or pursuing dreams of their own.”

It’s a great reminder, but I’ve found this to be a general truth in hiring, no matter what kind of team you’re trying to put together.

They also look at a number of team-building and team-dynamics issues through the lens of small companies — but again, maybe unnecessarily so, as these sorts of insights also apply much more broadly I think. “Acting with the team in mind is what sets great employees apart from good employees,” seems generally true, as does the great advice to “hire for mindsets over skill sets. For most positions, you can teach someone to do what you need done, but you cannot teach a person how to think.”

And while “being explicit about responsibilities is an imperative…in a startup, everyone is wearing lots of hats, but as you scale, clarity avoids misunderstanding and mistakes” is surely true, in my experience it remains true even when the scaling is done and the team is built. Without doubt developing the habits early will pay off, but being explicit and clear about responsibilities is always better than not.

“Stuff happens. How you respond to problems defines your future.”

The authors express a surprisingly harsh view of the notion of work-life balance. Which is to say, they utterly reject it as a goal.

“It comes down to our acceptance of a truth — ‘work-life balance’ is a myth. If your life is completely in balance (and whose is?), it’s like a seesaw standing still, our feet just dangling, going nowhere — and that’s no fun. It also means everything’s just average.”

It’s a bit of a no-pain no-gain attitude, I think. I get it. And there’s certainly something to the idea that if you don’t give your all, you give nothing. Half-measures are no measures. You’re either in it to win it, or you’re not. I get it…but I don’t necessarily agree with it.

“‘Work-life balance’ is a myth” feels out of step with some of the other reading I’ve been doing lately (Work Won’t Love You Back, or The Good Enough Job, for instance). And it’s almost antithetical to the various notions like “quiet quitting” that have been gaining some momentum since the pandemic, too. This might very well be one of those places where this notion is specifically more applicable to a start-up or microbusiness than to larger teams.

I was particularly taken with a couple of turns of phrase and twists on classic metaphors. For instance, the fairly tired metaphor of a “pivot” gets a nice reexamination:

“Many people think the word pivot means to change direction. But that’s incomplete. To an engineer, the word refers to the central point on which a mechanism turns. You keep an anchor foot on the floor when you turn…”

What a lovely reminder about the depth of the connotative value there.

I know I’m a sucker for digging into common metaphors, but I really think it’s valuable! They also look at the flip-side of a “glass ceiling,” which they brilliantly call a “sticky floor”:

“Often people in marginalized groups focus on the glass ceiling they have to break through to succeed. But self-doubt is a sticky floor. Your own lack of confidence can hold you down…”

Of course, they don’t shy away from talking about the specific challenges they see for women entrepreneurs and founders of color.

“If you are a white male founder and you make a mistake, it’s often treated as a dress rehearsal, and you’re given the chance to try again. Failure is almost seen as a badge of honor…But we know it’s often the opposite when you are a marginalized or disadvantaged business owner…One mistake is seen as a predictor instead of a practice run.”

Given this, it’s worth noting that as “marginalized or disadvantaged” entrepreneurs themselves, it’s especially bold and powerful that they frame the book with, literally, the story of their failed venture.

“It does no good for the captain of the ship to stop smiling.”

Anyway, throughout the book there are some eye-opening and timely stats, well-cited and pretty devastating (though hardly surprising) backing this up:

“Despite a renewed focus on racial inequality spurred by the Black Lives Matter movement in the summer of 2020, Black and Latinx founders raised just 2.6 percent of VC in the first ten months of 2020.”

“...women-owned ventures account for just 16 percent of conventional small-business loans and 17 percent of SBA loans, even though female-owned firms make up a third of all small companies in the U.S.”

“...companies led solely by women raised less than 2.2 percent of venture dollars, or $2.6 billion in the first eight months of 2021, a decline from each of the last five years. And just 0.034 percent of VC, or $494 million, went to female founders of color, according to data compiled by Crunchbase.”

“A 2020 Kauffman Foundation survey of people who came up with a business idea but abandoned it before starting revealed that 49 percent gave up because they didn’t believe the business would survive. Fifty-five percent of women quit before they started.”

In reference to impact on small business of the Covid lockdowns: “African Americans experienced the largest losses: a 41 percent drop in the number of active business owners. Latinx businesses also faced major losses: 32 percent. Immigrant business owners suffered a 36 percent drop, and female business owners 25 percent.”

With that said, since the story is about the failure of their business, I noticed that they were pretty philosophical about failing:

“Too often, the flaws feel personal, and entrepreneurs are hardwired to take the blame. If only I hadn’t…becomes a mantra, and I should have…echoes in like a claxon. Yes, we’ll make mistakes, but when the problem is in the system, you can’t take responsibility for not knowing before you could possibly know.”

That’s a refreshingly thoughtful sentiment.

“The weight of your word has to mean something. Without integrity, you have nothing.”

In the end, I wouldn’t say this is a critical volume in my project of understanding more about managing and leading teams of creative professionals — most of the key insights (and there are many!) are more applicable to manufacturing and retail, diving into systemic issues with capital, credit, supply chains, and the terrifying power dynamic between huge retailers and startup products. I’m glad I read it and I do think I got some good things from it, though, and came out of it an even bigger fan of Abrams.